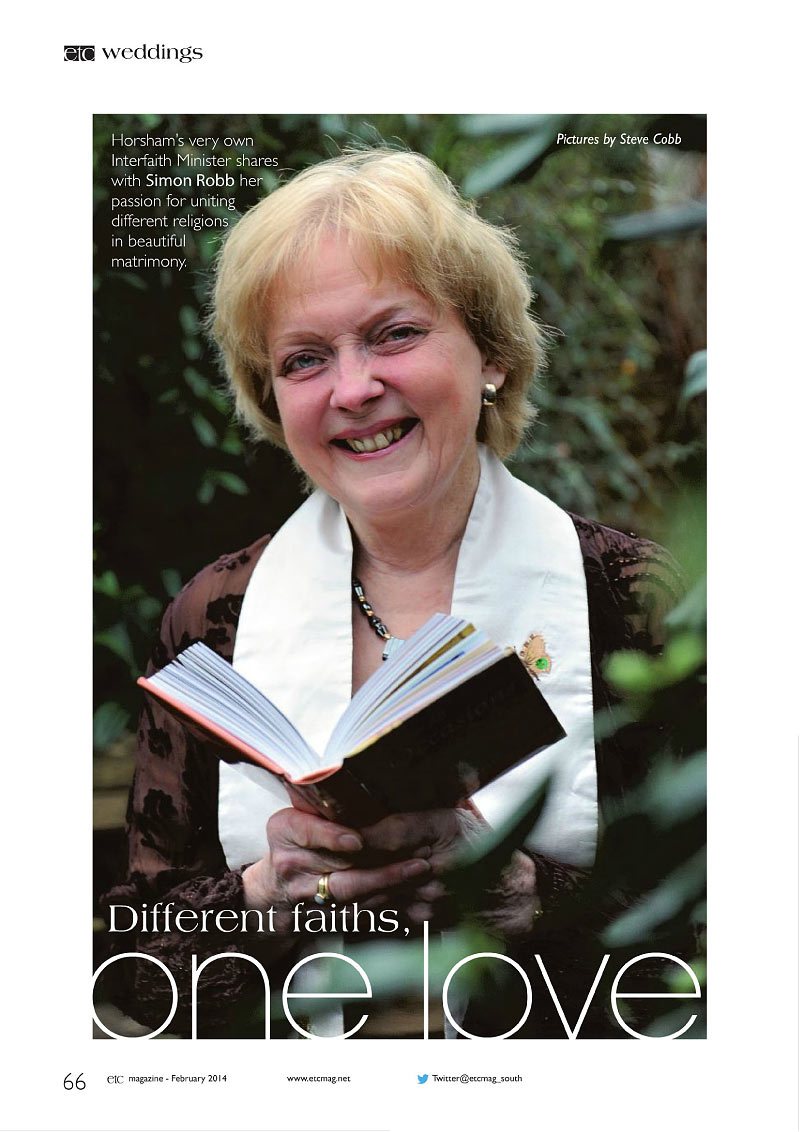

Horsham’s very own Interfaith Minister, Rev. Jean Francis, shares with Simon Robb her passion for uniting different religions in beautiful matrimony. Etc. Magazine published this article about Interfaith weddings in their February 2014 edition. Pictures by Steve Cobb.

Category Archives: News

The Healing Power of a Good Funeral

When Colin, my ex-husband was told he had only a short while to live he asked if I would write and conduct his funeral. I began to put words together and as I read them to him over the phone asked him to stop me if he wanted to make changes. During this process he opened up in a way I had never known, in all our years of marriage and it was like our hearts really touched for the very first time.

He spoke about the hardships suffered as a 13 year old on a naval training ship and his time spent in Korea during his National Service. As he spoke I could hear the pain in his voice as he remembered and verbalised the horrors for probably the first time. I began to deeply regret not having been more compassionate within our marriage. He had buried such traumatic memories that were now being allowed to surface as he surrendered to the inevitable. What a pity this conversation, which led to such a deep understanding, had not taken place many years before!

As we discussed in minute detail the message he wished me to deliver within the service, we changed words and refined the meanings and he was absolutely positive as to what he wished to be included or not. The service content was extremely personal and reflected his deep love of animals, fishing and the natural world. It concluded with a committal written especially for hm. See the order of service attached.

Just before his passing I sent him a letter of love and regret saying ‘maybe we’ll be better equipped the next time around.’ On the day of the funeral the funeral director caught my eye as I began to lead the coffin towards the catafalque, saying: ‘He has your letter in his hand.’

Having lived with so many painful memories he had finally, surrendered…

Colin and I had been divorced for 18 years, with our beloved dogs acting as our bridge to friendship.

Colin’s request that I play this role within his funeral was an honour and a profoundly healing experience for me and I truly believe for him too. I have always had an inner knowing that by discussing such arrangements prior to need, unique opportunities for adjustment and healing can be found, I now know! Faced with our demise we can think and speak more openly and honestly. Having looked death right in the face, we can get on and live our lives more fully, benefitting from the knowledge gained within the process.

To plan your own funeral prior to need or that of a loved one contact Jean.

Facebook reviews family memorials after dad’s plea

By Dave Lee Technology reporter, BBC News

A father’s plea to watch a video based on his dead son’s Facebook page has provoked the network to look again at how families can remember loved ones.

Facebook recently launched a Look Back feature that creates a video generated by popular moments on a person’s profile.

John Berlin posted a YouTube clip asking to see a Look Back video for his son Jesse, who died in 2012 aged 22.

After the plea gained support, Facebook told Mr Berlin a video would be made.

Mr Berlin, who is from Missouri in the US, was unable to create the video himself as he did not have access to his son’s profile.

Facebook said it would create one on his behalf using content Jesse had posted publicly.

“It worked I was just contacted by FB by phone and they’re going to make a vid just for us,” John Berlin wrote in a status update.

“They also said they’re going to look at how they can better help families who have lost loved ones.”

Following the incident, Facebook has said it is working on implementing further ways to deal with death on the network.

“This experience reinforced to us that there’s more Facebook can do to help people celebrate and commemorate the lives of people they have lost,” a spokeswoman told the BBC via email.

“We’ll have more to share in the coming weeks and months.”

‘Shot in the dark’

Mr Berlin posted a video to YouTube “calling out to Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook”.

“You’ve been putting out these one-minute movies that everyone has been sharing,” he said. “I think they’re great.”

He went on to explain his son’s death, and how he could not access his profile.

“All we want to do is see his movie. I know it’s a shot in the dark but I don’t care.”

The clip was posted to link-sharing website Reddit where it gained a lot of support. Mr Berlin posted his son’s obituary to allay concerns the clip may have been a hoax.

Local radio station Pix11 stepped in to put Mr Berlin in contact with Facebook.

Protected profiles

Facebook already offers a “memorialising” process for profiles of deceased users.

The service was introduced in 2009 after one of the social network’s engineers lost a loved one and felt the existing measures were not sufficient.

Under the current set-up, family members can use the site’s help centre to send links from newspapers or other sources confirming the news that someone has died.

Facebook told the BBC such processes were in place to ensure someone did not maliciously try to shut an account – and that there was an appeal process in place for the rare occasions when mistakes were made.

Memorialising means a user who has died will no longer appear alongside advertising, or in contextual messages – and friends will not be reminded of a person’s birthday.

Facebook does not hand over full access to a person’s account due to privacy concerns.

In the past, Facebook has come under criticism for displaying prompts to talk to people who were no longer alive.

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC

Ashes to Ashes, but First a Nice Pine Box

By JEFFREY M. PIEHLER

It didn’t go over well. Her first reaction — silence — quickly turned to blind anger. Then came demands for explanation, then commands to desist. Finally she fell silent again, this time not in disbelief but in punishing disapproval.

I hadn’t anticipated so much resistance. The plan didn’t seem so extreme to me — no more extreme, anyway, than my circumstances. I have incurable Stage 4 prostate cancer, which I learned I had at age 54. I’ve been living with it for 11 years, and in that time I’ve tried every conventional treatment and many trial ones. All in all, I think I have done extraordinarily well: I’ve been able to travel, to photograph, to write. On most days, I walk over four miles. And although I did have to give up my surgical practice, the extra time has let me become much closer to my family and friends.

My family, of course, remembers not just the positives but those dark days of sickness after chemotherapy, the reactions to drugs requiring resuscitation, and the hospitalizations for complications. While I like my edited version better, theirs cannot be dismissed.

What we all agree on, though, is that my journey is coming to an end relatively soon. The remaining treatment options are mostly minor modifications of previous failures. My bones are riddled with metastatic disease, and I’m starting to need pain medications. As we used to say in the medical business, I’m starting to circle the drain.

Yes, but why build your own coffin? When I mention it to others, most are distinctly uncomfortable with what they interpret as my abandonment of the “fight against cancer,” which by their reasoning must be the explanation for my continued survival. I must be giving up. That my motivation is the exact opposite eludes them. In fact, it is a project that I wish I had started much earlier.

I began to think about this aspect of my own funeral. I, too, plan to be present — though unviewed — at my service, as well as cremated. But I find comfort in simplicity and familiarity and, I suppose, purity. A little investigation showed me that most people are cremated in a cardboard container of some sort. My ecological conscience argued for recycled cardboard, yet that implied that my ashes would spend eternity blended with the powdered remains of ice cream containers, first drafts and pizza boxes. I’m sure one could do worse, but why not opt for a more elemental final mix: me and wonderful old wood.

Making my own coffin was the answer. A plain pine box. My own plain pine box. Creating something of beauty and purpose would be both a celebration of life and an acceptance of my death.

I knew immediately whom to contact: Peter, a beautifully untethered soul and a talented artist who works in wood. Untethered or not, some persuasion was required. He feared he might be contributing to something my wife and family would find abhorrent. He said that he would gladly help if I could obtain their approval, which I eventually did.

The pine boards, rescued from an old factory, were thick with dirt, oil and splinters. I was skeptical of resurrection, but when the boards were cut into strips, rotated and planed, each one revealed a new beauty, emerging from its own distinctive grain and knots and scents.

Peter’s and my growing closeness as friends mirrored the process of preparing the wood. We each spoke of what we wanted to accomplish with our remaining lives, and what we regretted in our pasts. The coffin slowly took on its recognizable shape, prompting me to speak of my fears of death and of leaving my family behind. In moments like this, we set aside the tools, and we would sit and talk quietly. Peter had fears also, different from mine, but no less worthy: Artistic creativity is a challenging basis on which to support a family.

Amid this, there were also wonderful moments of black humor: How much nose clearance is acceptable? How much will I weigh when I actually need this thing? Does it come with a lifetime guarantee? We even made T-shirts that read, “I’m dying to show you my latest project.” But even the most joyous laughter often merged with tearful embrace.

With time and almost without awareness, the quality of the coffin’s construction became a surrogate for our mutual respect. We selected each board with careful deliberation. We glued and assembled them meticulously, and adjacent boards were book-matched to present beautiful mirrored images of the wood’s grain. Finally everything was hand sanded and sealed with a natural finish.

We’d made a stunningly beautiful pine box, and a stunningly beautiful friendship. But we knew that neither could last, and that this was the very reason to celebrate them.

Something else has happened, too. The project has smoothed the rough edges of my thoughts. It’s pretty much impossible to feel anger at someone for driving too slowly in front of you in traffic when you’ve just come from sanding your own coffin. Coveting material objects, holding on to old grudges, failing to pause and see the grace in strangers — all equally foolish. While the coffin is indeed a reminder of what awaits us all, its true message is to live every moment to its greatest potential.

So the box now sits at the ready for its final task, when together we will be consigned to the flames. I find comfort in knowing where my body will lie, and just above it, embossed on the underside of the coffin’s lid, in front of my sightless eyes — my favorite line of poetry: “I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night.”

Father’s ashes taken in car theft

A couple have been left devastated after thieves stole their car and the ashes of the woman’s father. The couple had travelled to a friend’s house because it was raining so hard they ran inside leaving presents and the urn containing the ashes in the car. The husband said his wife’s father “travels with us to all significant family gatherings so that he can share in the occasion.” He added,” we appeal to the thieves to contact the police with the location of the ashes so that we can have my wife’s dad back with us.”

A police spokesman said: “We’re desperately looking to find this man’s car and his wife’s fathers ashes as well as the thieves that stole it.”

Tattoos could last more than a lifetime

Two years ago Floris Hirschfeld had a portrait of his late mother tattooed on his back. Now the Dutch man hopes the image will one day adorn the wall of an art collector’s home, with the help of an entrepreneur who has set up a business to preserve the tattoos of the dead.

The Healing Power of a Good Funeral

When Colin, my ex-husband was told he had only a short while to live he asked if I would write and conduct his funeral. I began to put words together and as I read them to him over the phone asked him to stop me if he wanted to make changes. During this process he opened up in a way I had never known, in all our years of marriage and it was like our hearts really touched for the very first time. Continue reading

Jean Wins A Major National Award

The Mexican Day of the Dead

As we approach Halloween I am reminded of probably my best holiday ever.

The Mexican Day of the Dead is know in Mexico as Dia los Muertos and is recognised as a national holiday. The festival takes place each year on All Saints Day, Nov 2nd. Festivities begin with children parading the streets in spooky costumes, while in the market places, homes and hotels beautiful alters are created to honour Continue reading

Whatever Next?

A coffin with boob room!